by Fr. Dennis Koliński, SJC

Note from Dr. Chervin:

The word “spirituality” means different things to different people. In the Catholic tradition we associate the word primarily with the witness and writings of great saints or other influential accounts of ardent Christians in their lives and words. Others may think of spirituality primarily as a personal quest for holiness. Although John Paul II was considered holy even by those outside the Catholic faith, not often has his life and thought been studied as a type of spirituality. At Holy Apostles, Fr. Dennis Koliński is admired mostly for his courses on liturgy, but he is also a fine confessor and spiritual director. I think you will find his article interesting and helpful.

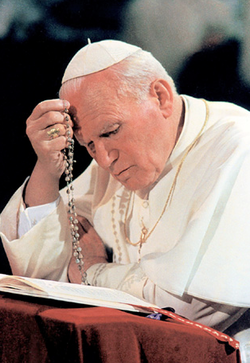

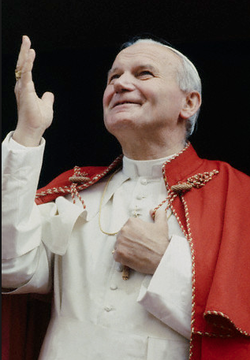

At his death, the people who had gathered in St. Peter’s Square, already sensing “the odor of sanctity,” spontaneously began to call out Santo Subito! For, not only was he a great intellect, perhaps one of the greatest of modern times, he was a charismatic figure, who knew how to connect with the crowds, especially youth. He was a person, who exuded holiness and whose life was so thoroughly immersed in Christ that people knew he lived in a unique, intimate relationship with him.

Saint John Paul’s teachings brought us many new insights into the faith. But these new perspectives were not only the result of theological reflection. They also often had roots in his own spirituality and the experiences of his life. Now that he will officially be counted among the ranks of the blessed in heaven, it will therefore be important to look more closely at his spiritual life to see what made him a saint and what gave him some of those great insights into our faith. And one cannot adequately speak about the inner spiritual life of this man without considering the complexity of his life and the large role that his native land played in shaping the life of his soul.

The Wojtyłas were devout Catholics, and from the beginning, they instilled a love of the faith in their children. They lived in a second-story flat next to the city’s main parish, Church of the Presentation of the Blessed Virgin Mary. Growing up in such close proximity to it helped cultivate Karol’s spiritual life from an early age. Every day he could see it from the windows of his home and hear the sounds of liturgies and devotions taking place within it. At an early age, he became an altar server and the church was like a second home to him.

However, when he was only nine years old, the tranquility of Karol’s childhood was suddenly shattered with the death of his mother. Instead of remarrying, his father, a retired officer from the Austro-Hungarian army, chose to raise Karol and his brother Edmund alone. He was to be a great influence on the formation of young Karol’s early spiritual life. According to Jerzy Klunger, Karol’s lifelong Jewish friend from Wadowice, the Captain’s outstanding characteristic “was that he was a ‘just man.’ And he believed he had a responsibility to transmit that commitment to living justly to his son.” During those formative early years, the elder Wojtyła had an enormous influence on Karol’s own spiritual development. He would remember his father as a man of constant prayer, whom he would often see praying silently on his knees late at night. His father’s example was for him, in a way, his “first seminary, a kind of domestic seminary.”

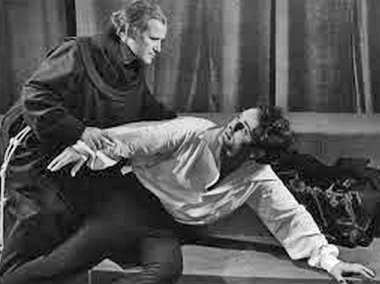

Wadowice was a regional center of literary life and theater, which began to interest Karol in his high school years. Mieczysław Kotlarczyk, one of the city’s theatrical directors, had a deep influence on Karol in “the relationship of the proclaimed word to the dynamics of history.” A devout Catholic, Kotlarczyk believed that drama was a means of “transmitting the Word of God,” and that the actor, by opening up the realm of transcendent truth, “had a function not unlike a priest.” One can already see in this the beginning of the development of a certain aspect of Blessed John Paul’s spirituality by means of which he began to realize the power of the word to transform history. As pope, he would write that the Word is the primary dimension of the spiritual life and that the word, even in a literary or linguistic sense, comes close to the Mystery of the Word.

After Karol completed high school in 1938, his father decided that the two of them would move to Kraków where Karol would begin university studies in Polish philology at the Jagiellonian University. It was a much larger city and center of culture where he was able to immerse himself in the theater and literary pursuits that so captivated him.

During the Occupation, the Nazis required all able-bodied men to have some type of employment or be shipped out to labor camps. So, when they closed down the university, Karol had to find himself a job. He began work at the Zakrzówek quarry on the south side of Kraków, and then, after a year there, was transferred to the nearby Solvay chemical plant in Borek Fałęcki where he worked for another three years. Up until this time, Karol Wojtyła had lived in the world of academia and the literary arts. But being forced to work with his hands was actually providential because it introduced him, for the first time in his life, to the world of manual labor and common laborers.

St. Stanisław Kostka Church in 1931

St. Stanisław Kostka Church in 1931 As the Gestapo systematically took priests of the parish off to concentration camps, the few, who remained turned to laymen to lead clandestine ministries within the parish. One of these men was Jan Tyranowski, a mystic who would have a decisive influence on Karol’s spiritual life. When Tyranowski created a “Living Rosary” for young men in the parish, he asked Karol Wojtyła to be one of its group leaders.

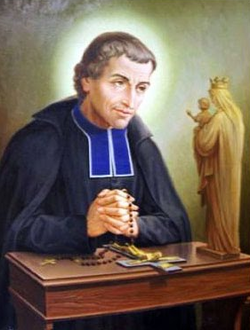

Tyranowski taught his group leaders both the fundamentals of the spiritual life and methods for systematically examining and improving their daily lives. … Members of the Living Rosary pledged themselves to a life of intensified prayer as brothers in Christ who would help one another in all the circumstances of their lives. … The Living Rosary groups also discussed how Poland might be reconstituted as a Christian society after the war.

Jan Tyranowski

Jan Tyranowski Perhaps, the greatest impact that Jan Tyranowski had on the spiritual life of the future pope, however, was when he introduced him to St. John of the Cross, sensing that the saint’s spiritual poetry would appeal to the young student’s love of literature. This, in turn, opened for Karol the door to Carmelite spirituality, which would have a profound spiritual influence on the rest of his life. It was a spiritual perspective that taught him “the imitation of Christ through the complete handing over of every worldly security to the merciful will of God,” [which] “would become the defining characteristic of his own discipleship.” And although it was Jan Tyranowski, who initially introduced Karol to the works of St. John of the Cross and St Teresa of Avila, this was not the only Carmelite influence in his life; for during those formative years, occasional visits to the Discalced Carmelite Monastery in Kraków would further imprint Carmelite spirituality on his spiritual life. Karol Wojtyła strongly felt that he was destined to be an actor—but that was not to be. His father’s death on February 18, 1941, was to be the decisive moment that changed the course of his life. The loss of his father, the last living member of his family, began a process of detachment in his life. Orphaned before he was twenty-one years old, amidst the harsh reality of war and an increasingly intense spiritual life, Karol gradually came to the realization that he was called to an even greater destiny: to the priesthood. Later in life, he would describe those years as “an evolutionary process of gradual clarification or ‘interior illumination.’” At first, he wanted to enter the Carmelites, but Cardinal Adam Sapieha, the Archbishop of Kraków, convinced him that a man with talents such as his belonged not in a monastery but among the people as a diocesan priest.

Cardinal Adam Sapieha

Cardinal Adam Sapieha On November 1, 1946, Cardinal Sapieha ordained Karol Wojtyła to the priesthood in his private chapel. The following day, the young Fr. Wojtyła set off for Wawel Hill where he offered his first three Masses on All Saints’ Day in the St. Leonard Crypt of the Cathedral.

His first assignment was as a curate in the Parish of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin in Niegowić, a small village southeast of Kraków. Only eight months later, the Cardinal transferred him to St. Florian’s Parish in Kraków to work as a chaplain to students of the Jagiellonian University. He was well suited to the job and had great success. But seeing Fr. Wojtyła’s talents, Cardinal Sapieha had other plans for him. Despite Wojtyła’s protests, the Cardinal released him from his duties at St. Florian’s in September of 1951 and gave him a two-year academic sabbatical to complete his habilitation thesis. After this, he began lecturing at the Jagiellonian University and the Catholic University of Lublin.

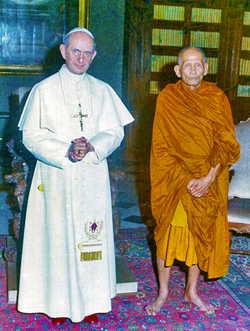

When Archbishop Baziak of Kraków died in June 1962, the young Bishop Wojtyła was then appointed temporary administrator of the archdiocese. Not long after this, he left for the opening of the Second Vatican Council where he played a key role in some of the Council’s discussions. On January 13, 1964, Pope Paul VI named him Archbishop of Kraków and then, three years later, raised him to the cardinalate.

The spirituality of this man who became pope from a hitherto little-known land, grew out of and has always been inextricably tied to the history and culture of his country. That is why it is virtually impossible to understand the inner spiritual life of Saint John Paul II without an understanding of Poland’s history and culture.

He also saw it as a profound theological moment, for those lying in the sarcophagi of Wawel Cathedral, were members of the Communion of Saints awaiting the resurrection from the dead. Among them were not only kings and queens, bishops and cardinals, but also the great bards of Poland, “great masters of the word, who possessed such enormous significance for [his] Christian and patriotic formation.”

As the Polish nobility began limiting the powers of the monarchy more and more, Poland’s three powerful neighbors, Russia, Prussia, and Austria began to grow in greed. In 1772, they signed a treaty by means of which they each took possession of a segment of Poland adjoining their country. In an attempt to reform and strengthen the government, the Polish Sejm (i.e., parliament) adopted the first democratic constitution in Europe on May 3, 1791. But by then it was already too late. In 1793, Russia and Prussia confiscated further Polish territories, and in 1795, the three powers adopted a joint agreement by which they divided up the remainder of what was left of Poland between them. Poland ceased to exist as a political state and entered into a long tragic era of its history called The Partitions. It would only be the beginning of two centuries of foreign occupation and suppression.

But Poland continued to exist in the minds and hearts of Poles, despite the fact that they were now divided between three different countries. In spite of efforts to de-Polonize them, Poles managed to maintain their national identity by keeping their culture alive. During this time, “the family became the mainstay of Polishness, which was clearly identified with Catholicism,” which in turn, became such an important part of that identity and so intertwined with Polish culture that before long, to be Polish meant to be Catholic.

The end of the war seemed to bring hope to many Poles, but even though they had fought on the side of the Allies, the Yalta Agreement turned their country over to the Soviets. A communist government was imposed on them and Poland once more became an occupied country, forced into servitude, this time by its old enemy to the east. Occasional uprisings in the 1960s and 1970s were suppressed until, in 1980, a strike in the Lenin Shipyard of Gdańsk led to the formation of Solidarność, the first independent trade union in the Soviet Block. It was a movement, which spread throughout the Eastern Block, eventually toppling the Soviet Empire. A decade later, Poland became an independent, free country once again.

This was the nation into which Saint John Paul II was born, a nation whose history and culture formed a distinctive Polish mentality and Catholic spirituality. The city, which he called home for forty years and which his heart never really left, was an integral element of that Polish history and culture, which would shape his personal spirituality.

St. Mary's Basilica in Krakow

St. Mary's Basilica in Krakow Kraków had always been a great center of culture in Poland. It was the place where Karol Wojtyła’s own cultural talents and sensitivities matured. It was there that he learned that culture had always played a vital role in the faith, fully conscious that it had also played an important role in the shaping of his own spirituality.

Because of its numerous churches, monasteries, shrines, and miraculous images, Kraków was often called the “Rome of the North.” Since the tenth century it was already a prominent center of Christian pilgrimage. But the fifteenth century, in particular, was a unique and blessed period in the city’s spiritual history. Known as Felix saeculum Cracoviae—“the happy century of Kraków”—it was a period when a number of mystics, later canonized or beatified, lived there. Some of them played an influential role in the spirituality of Saint John Paul II.

Born in 1390, St. John of Kęty (as he is also known) studied at the Jagiellonian University and then later spent the rest of his life there as a professor of philosophy and theology. Saint John Paul, therefore, saw in the saint a model of what he himself was: a philosopher and a theologian. Throughout his many years in Krakow, he visited the saint’s tomb in the beautiful Church of St. Anne many times and there drew much inspiration from his own patron saint of learning. It was no surprise, therefore, that during his 1997 pilgrimage to Poland, he made a point of visiting the tomb of St. John Cantius, where during a special gathering with professors of the Jagiellonian University, he alluded to the saint, saying: “Knowledge and wisdom seek a covenant with holiness.” It was in St. John of Kęty, that Saint John Paul saw clearly that Christian faith and the pursuit of human knowledge were not mutually exclusive, as many think today. It was the same thought that produced his famous encyclical, Fides et Ratio.

That same perspective revealed itself especially in Saint John Paul’s love for young people and students that he shared with the Saint from Kęty, who once wrote:

What kind of work can be more noble than to cultivate the minds of young people, guarding it carefully, so that the knowledge and love of God and His holy precepts go hand-in-hand with learning? To form young Christians and citizens—isn’t this the most beautiful and noble-minded way to make use of life, of all one’s talents and energy.

St. Stanislaw was the Thomas Beckett of Poland, suffering martyrdom in 1079 at the hand of King Bolesław Śmiały, an evil and psychologically tormented man, who wanted to restrict the Church’s authority. But because Stanislaw would not cede to the king’s demands, he murdered the bishop as he offered Mass. That’s why, in the face of an evil communist government that wanted to limit the authority of the Church in Poland, Archbishop Wojtyła very much saw himself as a modern-day Stanislaw fighting for the rights of the Church.

The young Karol Wojtyła had served Mass for his confessor and spiritual director, Fr. Kazimierz Figlewicz at the altar in front of the Black Crucifix. He spent time in prayer before it, just as Queen Jadwiga did. When the cardinals approached him in the Sistine Chapel that fateful day in October 1978, asking whether he would accept their choice of him as Supreme Pontiff, he didn’t want to leave his beloved Kraków, but perhaps he remembered what Christ had told Jadwiga “Fac quod vides.”

Brother Albert had always held a certain “spiritual attraction” for the young Karol Wojtyła, who at the time when he himself was beginning to leave the world of art—literature and the theater—found in Brother Albert “a certain spiritual reinforcement and model of the radical choice found on the road to a vocation.”, While stationed at the Church of St. Florian, the young Fr. Wojtyła was inspired by the life of Brother Albert to write his play “Our God’s Brother.”

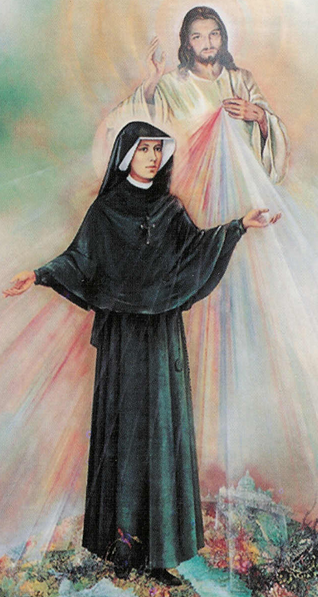

St. Faustyna Kowalska, who lived and died in the shadow of the Solvay Chemical Plant where Karol Wojtyła worked during the war, helped open up for him, in turn, the riches of God’s infinite mercy, that divine attribute, which a priest must also possess if he is to be “another Christ.” It is no surprise, therefore, that one of his first encyclicals as pope was Dives in Misericordia, which is “the clearest expression of the pastoral soul of John Paul II, and the clearest indication of how that soul was formed by Karol Wojtyła’s experience and understanding of fatherhood.”

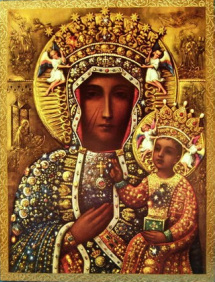

The Poles always refer to her as Matka Boża, “Mother of God,” and she is portrayed in Polish iconography almost exclusively as a Mother, holding the Christ Child on her arm. But the Poles see her not only as the Mother of Christ. She is also very much their own Mother. Even when portrayed as Queen, she was never someone unapproachable because of her lofty status, but rather someone to whom they could always turn in their most intimate needs.

Mary also holds a privileged place in Polish culture as Queen. Already in the fifteenth century Polish historian Jan Długosz called her Regina mundi et nostra. This was formalized in 1656, during the “The Deluge” when the Swedes overran the country and King Jan Kazimierz, in an official royal act, placed his country under Mary’s protection and named her Queen of Poland, an official title which she holds even to the present day.

Saint John Paul first learned traditional Polish Marian devotion at home and in the parish. During his grade school years in Wadowice, he and his fellow students would stop at the parish church on the way to school each morning and once again upon returning home in the evening, to pray in front of a revered image of Our Lady of Perpetual Help found in a chapel at the back of the church. He also learned of Our Lady of Mount Carmel in a Carmelite monastery that he would occasionally visit on the outskirts of town.

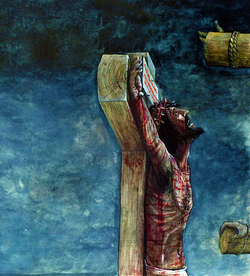

Whereas Saint John Paul’s Marian devotion is well-known, few people, however, know of his intense devotion to the Passion of Our Lord. As Archbishop of Kraków he would often walk to the Franciscan Church across the street from the Bishop’s Palace to pray the Stations of the Cross. But to fully understand this aspect of his spirituality, we need to return once again to Kalwaria Zebrzydowska, not only a Marian shrine, but foremost a shrine to the Passion and Death of Christ. Often called the “Polish Jerusalem,” it began in 1600, when Mikołaj Zebrzydowski, a devout aristocrat, began building chapels and small churches representing Jerusalem’s Via Crucis on a vast tract of his land that he thought resembled the topography of the Holy City. And ever since then, every year during Holy Week, mystery plays reenacting the Lord’s Passion would move from one station church to another amidst vast crowds of pilgrims, who became a part of the Passion drama.

Throughout his life, he would return to Kalwaria time and time again. In an address that he gave in Kalwaria Zebrzydowska during his pilgrimage to Poland as pope in 1979, he said:

Kalwaria Zebrzydowska: the sanctuary of the Mother of God and its stations. I visited them many times, beginning in the years of my boyhood and youth. I visited them as a priest. I visited the Kalwarian sanctuary particularly often as Archbishop and Cardinal of Kraków … I knew that I had to come here more often, first of all because there were more and more such matters, and secondly because—strangely enough—they usually resolved themselves after my visit to the stations. … The mystery of the Mother's union with her Son and of the Son with his Mother is seen [here]. … Whenever I came here, I always had the realization, that I was plunging into this reservoir of faith, hope, and charity, which were brought to these hills, to this sanctuary, by whole generations of God's People from this region from which I myself originate.

The influence of Kalwaria Zebrzydowska on the formation of Saint John Paul II’s Marian and Passion spirituality cannot be overestimated. In fact, his spirituality cannot be adequately understood without it. Even as bishop of Rome he continually returned there in his heart. Encapsulating the mystery of this sacred shrine so well during a visit there in August of 2002, he said:

In a mysterious manner, this place tunes the heart and mind for entering into the mystery of that bond, which united the Suffering Savior with his Mother, who shared his suffering. And in the center of that mystery of love, everyone, who comes here finds himself, his life, his own daily rhythm of life, his weakness and at the same time, the strength of faith and hope—that strength, which flows from the conviction, that the Mother will not abandon her child in adversity, but leads it to the Son and embodies his compassion.

“Poles show a clear tendency to highlight sufferings as the key to the nation's philosophy of history. For more than three centuries suffering has been a constant historical determinant of Poland and the price paid for patriotism.” In the seventeenth century, the Swedish “Deluge” swept across Poland, destroying churches, castles, cities and villages. It was something from which Poland was never able to fully recover. Then, at the end of the eighteenth century, when Poland was brutally ripped apart in The Partitions, the loss of political independence intensified the sense that suffering was the lot of the Polish nation.

By the time he entered the seminary, Karol Wojtyła had encountered a great deal of suffering. He lost his mother when he was only a child, then his brother and finally his father. At his father’s funeral, he remarked: “I never felt so alone.” Life during the Nazi Occupation was characterized by suffering. Shortages of food meant that most Poles lived in a state of constant hunger. The amount of coal allotted was barely enough to keep the chill out of homes and apartments during the bitterly cold winters. Many people, including Karol, had to work long grueling hours in sometimes inhuman conditions. He saw death everywhere in wartime Kraków: professors, priests, religious, laity, young and old arrested at a moment’s notice and then executed. His Jewish friends were rounded up and sent to Nazi death camps. Innocent people were killed by air raids and the lives of many courageous young people, some of them his personal friends, snuffed out as they tried to resist the oppressor through the Polish underground. And there were times when he asked himself: “So many of my friends have perished, and why not me?”

Although Saint John Paul II expected suffering in his life of one kind or another, he kept hearing Christ tell him through the Gospels: “Fear not!” He once wrote:

The Gospel is not a promise of easy success. It does not promise a comfortable life to anyone. It makes demands and, at the same time, it is a great promise—the promise of eternal life for man, who is subject to the law of death, and the promise of victory through faith for man, who is subject to many trials and setbacks.

The Polish Messianism that helped form the spiritual life of Karol Wojtyła said that Poland had a special role to play as a defender of Christianity and that this role required that it suffer. Through the intense suffering of his own life, when he lost “every other security and plunge[d] into a kind of radical emptiness,” Karol Wojtyła gradually began to realize during the intense purification of World War II, that perhaps God was calling him to a special mission, that perhaps he had a special role to play in God’s plan—that perhaps, God was calling him to become a priest, another Christ, and to offer up his life in a similar manner for the salvation of men. It may be that he kept telling us throughout the years of his pontificate, “Be not afraid,” because in the crucible of wartime Poland he discovered that if he abandoned himself totally to God, he would have nothing to fear, for he would gain what was most important—God himself. Karol Wojtyła saw his priesthood as both a great mystery and a great gift. It was the mystery of being chosen by God. For, as Christ once said, “It was not you who chose me, but I who chose you and appointed you to go and bear fruit.” (John 15:16)

One could, perhaps say, that by the time of his ordination, the spirituality that would influence the rest of Saint John Paul II’s life had essentially taken shape. There was, however, one other aspect of his spiritual life that would not be yet emerge fully until several years into his priesthood: something we might call his spirituality of the body.

When Fr. Wojtyła was assigned to St. Florian’s Parish in Kraków, he immediately began to work with the young university students, who frequented that parish. He taught them about the faith but as they came to him to discuss the most intimate details of their lives and the struggles they were dealing with, especially in their relationships, he also learned much from them about the relationships between men and women. Little-by-little a spiritual perspective on the relationship of the body to the soul in interpersonal relationships gradually began to emerge in his mind, which many years later crystallized into his teachings on the theology of the body.

Although it perhaps looked as if this was something completely new, something totally different, it really wasn’t. In a sense, it reflected the Carmelite spirituality that had such a large impact on Karol Wojtyła’s own spiritual life. For, he thought, if we are made for God, then we have to abandon ourselves completely to him, body and soul, in an act of complete love. And only in that way will we be able to enter into that total union with him for which we are all destined. This he understood in his own life by the total gift of his body and soul to the priesthood.

What he would later formulate in theological terms was born out of a spiritual perspective on the intimate relationship between the body and the soul. His understanding of this relationship wasn’t just a moral code to be followed. It wasn’t just a promise that he made at his ordination. Rather, it was a lived experience in the spiritual life of Karol Wojtyła that could rightly be called a spirituality of the body, a spirituality recognizing that the integrity of the human person includes both the body and the soul.

Saint John Paul II was born into in a unique Catholic culture that was lived intensely by the Poles of his era, a culture that reflected the soul of the nation, and that would, in turn, form his identity and profoundly influence his spirituality. It was a spirituality rooted deeply in the history of his nation and inspired by saints, whom he encountered along the path of his life. It was thoroughly permeated by a Marian and Passion spirituality, grounded not only in great mystics like St. John of the Cross and St. Louis Grignon de Montfort, but also in the spirituality of his country that he learned from the various spiritual masters that crossed his path. The spirituality of Saint John Paul II was like a rich tapestry woven from many different threads, revealing for us the inner life of a great modern mystic, who has much to teach us about the inner life of the soul.

A deep faith determined not only Saint John Paul’s perspective on the destiny of the world, but also on his own life, in which the principal dimension of his spirituality was “his living bond with Jesus Christ … [for] thanks to this complete union with Christ [he] became like a reflection of him.” He was convinced that everything that took place in his life was the realization of God’s designs.

The twentieth century was an era of overwhelming scientific and technological progress, but also of unprecedented horrors and confusion. As people have tried to make sense of it all, they sought meaning, consolation, and sometimes escape, in various forms of spirituality. Many have sought refuge in vague, esoteric spiritualities that are not grounded in the realities of the human person and the inner workings of the soul. Too few, however, influenced by fads and the promise of some kind of inner gratification, have questioned whether a this or that spiritual path is the best road that can be taken. Too few have asked: are the principles of a given spirituality valid and are they rooted in truth?

Although this look into Saint John Paul’s personal spirituality opens up for us the spiritual life of only one individual, it nonetheless, shows us the type of qualities that we should like to see in Catholics of the twenty-first century. By letting the life of Saint John Paul II speak for itself, we have an example of what we might call Catholic realism that can help guide us on our own individual spiritual paths and show us some of the equalities that we should hope for in this new era.

Saint John Paul II was “Great” not just because he had a great intellect. He was also great because of his great sanctity. He learned theology from study but came to a far deeper understanding of the faith on his knees, which is where one learns not just what God teaches us, but how to think as he does. Blessed John Paul was a great mystic, who lived his life in intimate union with God, who taught him how to think as he does. Saint John Paul’s spirituality was the way in which he lived that union in a unique way and by coming to a better understanding of it we can catch a glimpse into the very soul of a saint.

1. What are the primary defining characteristics of Saint John Paul II’s spirituality?

2. What are some of the aspects of Saint John Paul II’s spirituality that have found expression in his writings as pope?

3. Marian devotion is characteristic of many great saints and, as evidenced in Saint John Paul II, the context in which it was fostered has been an important determining factor of the role which Mary plays in their lives. What is the character of your own Marian devotion and what helped shape it?

4. “Spirituality” is a word used very loosely today and can mean almost anything that one wants. What is a true understanding of “spirituality,” especially in the sense of “Catholic spirituality?”

Response from Tommie Kim:

I have personally obtained most of my knowledge of the Christian faith and spirituality of Saint John Paul II’s spirituality through his writings. I was actually in Rome during the last minutes of Blessed John Paul II through his funeral. I was deeply impressed with thousands of young people that gathered from all over the world shouting together “sancto subito”. In 2000, I attended the beatification mass for Jacinta and Francisco. Prior to those days, I was able to attend his lectures and homilies when Pope John Paul II visited Catholic University in Korea. In addition, I have always enjoyed his lectures and homilies through Catholic websites and radios. I count it as one of the greatest blessing to have lived in the same era as Pope John Paul II.

In order to understand the spirituality of anyone, I agree that it requires an understanding of that person’s historical background as well as the family influences from youth. The history of Poland and its long years of suffering do help me understand that Poland was a country chosen by God for a purpose. Had there been no Polish history we may not have had such great saints and Pope of all times. It was even more amazing to realize the fact that the faith of the Poles deepened and strengthened further with suffering. Poland is identified as a martyred and crucified nation. And the Poles participated in the suffering as they were chosen by God to take special role as defender of Christian faith. I remember seeing a video of Pope John Paul II on his 7-day journey that changed the world. The most impressive message was how Poles were able to become strong even at a sight of a cross. The cross was the source of strength for the Pole. After the shooting attempt at the Vatican, Pope John Paul II gave a homily at the Fatima. He mentioned that in God’s providence, there is no coincidence. God’s grace has protected the Pope on the day of the shooting. “The Gospel is not a promise of easy success. It does not promise a comfortable life to anyone. It makes demands and at the same time, it is a great promise – the promise of eternal life for man…”

RSS Feed

RSS Feed